The U.S. Mints

History of the U.S. Mints

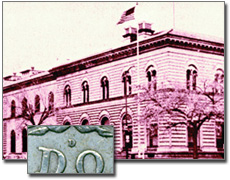

America’s first mint started operations in Philadelphia in 1793, and cents and half cents were the very first U.S. coins struck for circulation. Once the site of a former brewery, that mint (shown right) was very different from today’s mechanized facility. All the dies were cut by hand, and each die cutter would add his own touches. A screw press was used to squeeze the planchets between the obverse and reverse dies. Horses or strong men powered the press, and the mint’s security system was a ferocious dog named Nero!

1st Philadelphia Mint

Today, four different U.S. Mints strike coins, while four others have struck coins in the past. A small letter or mint mark on coins identifies the mints that struck them. These marks date back to ancient Greece and Rome. Mint marks on U.S. coins began with the passage of the Act of March 3, 1835. This established our first branch mints, and mint marks appeared on coins for the first time in 1838.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

1793-Date, “P” mint mark

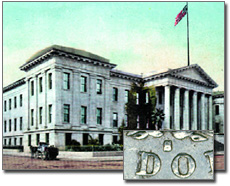

2nd Philadelphia Mint, 1833-1901

The history of the United States Mint in Philadelphia stretches back to the time when George Washington was president and our nation's capital was Philadelphia. The establishment of the U.S. Mint was provided for in the Act of April 2, 1792. The first coins struck at the original mint in Philadelphia were minted, according to popular belief, from silver household plates personally delivered by President Washington himself!

The Philadelphia Mint was the first public building erected by authority of Congress. The mint remained in Philadelphia after the federal government was relocated to Washington, D.C., although debates continued for the next 28 years between advocates who believed the mint belonged in the national capital and opponents who insisted it stay in Philadelphia. On March 10, 1828, Congress authorized the mint's continuation in Philadelphia until otherwise provided by law, which finally laid the issue to rest.

A watchdog named Nero was purchased for $3 and, together with a watchman, provided security for the first mint. Construction began in 1829 and the new, larger mint was in operation for 70 years. As coinage production increased, the U.S. Mint expanded twice more in the city of Philadelphia.

This has always been the main U.S. Mint facility. Most coins struck here have no mint marks. The exceptions are the Wartime nickels of 1942-45, Anthony dollars of 1979, and all Philadelphia coins since 1980 except the cent, which continues without.

Denver, Colorado

1906-Date, “D” mint mark

In 1862, the government purchased the Clark-Gruber banking facility for $25,000 with the intention of establishing a branch mint. However, due to hostilities with Native American tribes, the Denver facility was never able to function as a branch mint. Instead, it became an assay office, opening in September 1863. Miners brought in their gold, then it was melted and made into bars. The bars were stamped with the fineness and the inscription "U.S. BRANCH MINT, DENVER." In 1877, the building had deteriorated. This, along with major gold and silver discoveries in Colorado, finally led to the establishment of a real Denver Mint. The building – which was completed in 1904, began production in 1906, and was enlarged in 1937 – enabled Denver to set a record in 1969, when over 5 billion coins were produced there.

West Point, New York

1984-Date, “W” mint mark

The West Point Mint was erected in 1937 as the West Point Bullion Depository for the storage of silver reserves, and for many years had the nickname "The Fort Knox of Silver." The facility produced Lincoln cents bearing no mint mark from 1973-1986, and began striking U.S. commemorative coins with a $10 gold piece honoring the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. In 1988, West Point gained official status as a branch United States Mint.

Today, the West Point Mint stores U.S. gold bullion, strikes gold and silver U.S. commemorative coins with "W" mint marks, and produces the entire family of silver, gold and platinum American Eagle coins in both Uncirculated and Proof versions. A 1996-W Roosevelt dime commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Roosevelt series was issued only in that year's Mint Sets, and it remains the only regular-issue U.S. coin with a "W" mint mark.

Due to the presence of substantial gold reserves, security at the West Point Mint is extremely tight. Like the Fort Knox Bullion Depository, access to the site and tours are not available to the public.

San Francisco, California

1854-Date, “S” mint mark

The California gold rush of 1848 caused chaotic conditions as the amount of gold being mined increased rapidly and in dramatic proportions. Gold was heavy and difficult to transport to the Philadelphia Mint, and encountered many hazardous moments on its journey. A number of private mints took advantage of the situation and quickly produced coins that circulated in great quantities. In order to take control, the federal government quickly authorized a branch mint in San Francisco.

2nd San Francisco Mint, 1874-1937

A small plant was built, and operations began in 1854. The tiny mint was unable to meet the demands of the West and construction was begun on a new, larger mint in 1872. Two years later, the new branch mint was ready. Immediately upon its opening, the mint was dubbed the Granite Lady, a tribute to its size and architecture. The massive building was one of the most luxurious mints in the world, featuring gold and bronze chandeliers and 14 marble fireplaces on the first and second floors. Its massive structure and architectural strength were put to the test thirty years later.

On April 18, 1906, San Francisco was twisted, broken and burned by the worst earthquake ever to rock the United States. The Granite Lady survived the quake due to its solid construction, but the real threat was the aftermath – fire! Because of its thick granite walls and metal window frames, the mint was thought to be immune to fire. But the incredible heat began to shatter the windows and melt the frames. Underneath the mint's vaults was an artesian well, but the shock of the earthquake had broken its pump. Repairing it enough to be operated by hand, some volunteers filled buckets and threw water on the interior woodwork, which had ignited when the windows blew in. On the roof, men with iron bars, picks and shovels tore off tar paper and threw it to the ground. The exposed roof beams were then saturated with a fire-retardant liquid.

After seven hours, the Mint was blackened and its iron shutters twisted by the heat. But the Granite Lady was safe, still standing in the midst of the devastation that was San Francisco. It was a difficult period for the whole city – many people had lost everything, and most had no access to their savings. Bank safes took weeks to cool enough to allow access to their contents. Since the mint was one of the few buildings to survive – and the only financial institution left – it became a temporary bank and handled much-needed relief funds for the city.

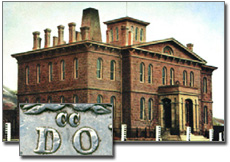

Carson City, Nevada

1870-1893, “CC” mint mark

The Comstock Lode of Virginia City, Nevada, was such a large strike that a branch mint was set up in nearby Carson City, named after the famous frontiersman Kit Carson. This Nevada mint was a short-lived facility and produced some of the scarcest coins in numismatics. During its years of operation, the Carson City Mint gained a reputation for striking some of the most finely detailed, high-quality coins in U.S. history. The Morgan silver dollars that were struck here are considered to be the finest in the series.

Carson City, today the capital of Nevada, was founded by a colorful character named Abraham Curry. Curry was a shrewd businessman who bargained and fought tirelessly to improve and develop the city. He finally convinced the federal government to build a branch mint in Carson City to handle Nevada's large silver supply. Congress authorized $150,000 for the project in 1866, and Abe Curry became the general contractor for construction. The mint ended up costing three times the original amount, but it was a fortress.The concrete foundation extended seven feet below the basement floor and the sandstone walls were four feet thick! When the mint opened in 1869, general contractor Curry went on to become its first superintendent.

The Carson City Mint has produced some of the scarcest coins in numismatics. Its colorful and exciting era ended in 1893, when the Comstock Lode began to give out. Today, the Carson City Mint is a museum, opening its doors to half a million visitors each year.

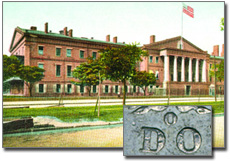

New Orleans, Louisiana

1838-1909, “O” mint mark

The U.S. branch mint in New Orleans has a history as colorful and interesting as the city itself. Established as the commercial and financial center of the entire South, New Orleans wanted monetary independence from the northern banks and the Philadelphia Mint. Heated debates raged between northern and southern senators over the need for a mint in New Orleans. Southern congressmen stood their ground and a New Orleans branch of the U.S. Mint was authorized in 1835.

A stately building occupying an entire block was built next to the famous French Quarter on the banks of the Mississippi River. Coinage operations began in 1838 and then were suspended for much of 1839 when a yellow fever epidemic caused the mint to close. By 1860, relations between North and South had become very tense. In January of the next year, Louisiana became the second state to secede from the Union. Within a week, the state of Louisiana took over the New Orleans Mint. Some mint employees, still loyal to the Union, destroyed a number of dies.

Two months later, the Confederacy took over the mint. This was the third government in ten weeks that had control over mint operations! The Confederate mint struck coins only until May of 1861, then was closed as soldiers raided it for war material. After the Civil War, the New Orleans Mint stood unused until 1876 when it opened as an assay office.

In 1878, the U.S. government regained control of the New Orleans Mint and President Rutherford Hayes appointed Henry Stuart Foote superintendent. A southerner with a broad background in both politics and law, Foote was an ideal candidate to bring the mint back to life. After 18 years of ceased coin production, much of the mint's equipment had succumbed to misuse. In addition, Foote faced significant delays in repairs due to an epidemic of yellow fever that had plagued the area. Nonetheless, he was able to get production under way, and in 1879, the first post-war coins rolled off the presses. First to be released were the "O" Mint Morgan dollars; then came the $10 and $20 Liberty Head gold pieces. Fewer than 2,400 of both gold coins were struck that year, and today these issues are considered extremely rare and sought after by collectors. In fact, it is estimated that only 12-15 of the 1879-O $10 gold pieces still survive today.

Foote served as the New Orleans Mint superintendent until his death in 1880. Despite his efforts, coin operations ended in 1909 because the more modern San Francisco and Denver Mints could better handle production. The building still stands on the banks of the Mississippi and is today a museum.

Charlotte, North Carolina

1838-1861, “C” mint mark

A branch U.S. Mint was established in Charlotte, North Carolina for the exclusive production of gold coins following the discovery of gold in the Carolinas. Opening in July 1837, the Charlotte facility processed and refined raw gold until March 1838 – when $5 gold half eagles became the first U.S. coins with the "C" mark of the Charlotte Mint. Later that year, $2.50 gold quarter eagles went into production, and gold dollars were added to the output in 1849.

When North Carolina seceded from the Union in May 1861, the Charlotte Mint was taken over first by the State of North Carolina and then by the Confederacy. Bullion supplies ran out a few months later, and the building was turned into military space and a hospital for Confederate troops. After the Civil War in 1867, the U.S. government converted the mint to an assay office.

When scheduled for demolition in 1931, a group of citizens acquired the structure from the U.S. government, relocated it to a new site in Charlotte, and in 1936 opened the Mint Museum of Art. Among the displays is a complete collection of U.S. gold coins struck at the former Charlotte Mint – all of which are scarce to extremely rare, and highly prized by collectors.

Dahlonega, Georgia

1838-1861, “D” mint mark

A branch U.S. Mint was established in Dahlonega, Georgia for the exclusive production of gold coinage after gold deposits were discovered in the nearby area. The first coins struck at the Dahlonega Mint were $5 gold half eagles in 1838, and $2.50 gold quarter eagles were issued by the Georgia facility beginning in 1839. Gold dollar production commenced in 1849, and $3 gold pieces were struck for a single year in 1854.

When Georgia seceded from the Union in 1861, the state took over the Dahlonega Mint's building and machinery. The Confederate Congress closed the facility in June of 1861, and for the duration of the Civil War, an assayer lived in the old mint and acted as caretaker. The structure was occupied by federal troops during the Reconstruction era after the war, and in 1873 the U.S. government donated the facility to North Georgia Agricultural College (now the University of North Georgia). The structure served as the college's main academic and administrative building until it burned in 1878. A new college facility was erected on the granite foundation of the former Dahlonega Mint.