How Coins Are Made | Ancient to Modern Times

How Were Ancient Coins Made?

The earliest Roman coins and some Biblical issues were cast coins, meaning they were formed by pouring molten metal into molds and allowing the metal to harden. Ancient Roman coins were cast until about 211 B.C., when the method of production changed to hand-held dies and hammers.

The design for one side of the coin (usually the obverse) was engraved into a metal disc or die, which fit into an anvil. The design for the other side (usually the reverse) was carved into the base of a metal punch. Though some dies were made of iron, engraving in iron was difficult. So dies made of bronze were far more prevalent.

These Roman silver Antoninianii were struck using hand-held dies and hammers.

The planchet is positioned on the anvil die with the punch positioned over it.

A planchet, or coin blank, was made by pouring molten metal into a mold, then allowing it to cool and harden. The blank was reheated to soften it for striking, then placed on the anvil die with the punch positioned over it.

With one or more sharp blows from a hammer, a coin was created – although with varying degrees of quality.

For the images to transfer cleanly and squarely, a lot of things had to go right. The coin blank had to be heated to the right temperature. The die and punch had to be properly aligned. The planchet had to be properly centered. And the hammer had to find its mark with precision.

Not surprisingly, this hand-struck technique often resulted in weak or off-center strikes, as well as misaligned strikes when more than one hammer blow was issued.

And as a result, nearly every ancient coin is unique, being slightly different from any other!

Industrial Advances in Coin Production

Mechanical coin presses were devised in the early 16th century and took two distinct forms. The roller press featured two horizontal steel cylinders, between which a strip of metal of uniform thickness would pass.

Each cylinder featured engraved obverse or reverse designs, equally spaced around the roller circumference. Perfect alignment between the two cylinders was essential as the planchet metal moved between them.

In the early 1800s, roller presses were replaced by large screw presses. These required coordinated teamwork to operate. Four men had to work together to spin two swinging, weighted arms to power the press. The coiner placed the blank in the correct position for striking, then removed it by hand after striking.

If the timing was off, the team risked more than a miscoined planchet. Loss of fingers was an occupational hazard. So the coiner had to be fast!

These ways of minting coins were vast improvements in many ways over ancient methods. But there was still room for improvement. Coins made this way had no reeded or grained edges, so clipping (shaving small pieces of metal from the coins) still occurred.

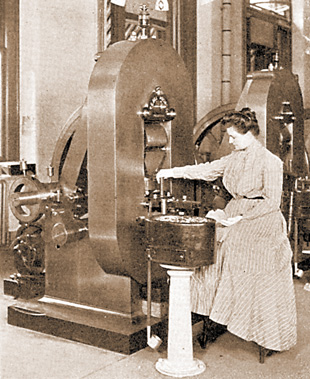

Hand-operated roller and screw presses were replaced during the Industrial Age with steam-powered coin presses developed by Matthew Boulton and James Watt. These new presses used a "toggle joint" mechanism, yielding far greater pressure upon the planchets (coin blanks) than the screw press operated by humans or horses.

What’s more, the coin blank was now automatically placed in the center of the die, where a collar impressed graining on the coin's edges. Not only did this invention enable mints to produce thousands of coins. It cut down on the centuries-old problem of clipping.

Used throughout most of the 19th century, these steam presses corresponded with the era of steamships, steam-driven locomotives and even early steam-driven automobiles.

Steam presses, using lever power rather than hand power, were introduced at the Philadelphia Mint.

The Modern Age

The modern minting process requires the refinement of metal to specific proportions, then rolling it into strips from which coin blanks or planchets of precise size are cut. The rolling process requires a process of heating and cooling – known as annealing – which brings the metal stock to the consistency needed for shaping and stamping.

Once the coin blanks are cut from the metal strips, they are polished and "pickled" in a centrifugal finishing machine that tumbles the planchets with stainless steel balls and special chemicals to burnish and brighten the surfaces in preparation for coining.

Coins are still struck from dies. But today’s dies are cylindrical pieces of hardened steel bearing the recessed design, date and other inscriptions upon one end. To make the dies, an artist first creates a large plaster model of the coin, from which a metal model called a galvano is made.

The galvano, which measures approximately 8 inches in diameter, is attached to one spindle of a reducing lathe, while a steel cylinder the diameter of the actual coin – called the master hub – is attached to another spindle.

A spinning stylus then reads the large galvano image while a spinning cutter device engraves the design onto the steel master hub. A number of "working hubs" with raised images and inscriptions impress blank steel cylinders with recessed designs – creating the "working dies" that actually strike the coins.

To mint the coins, the dies are mounted in an electric or hydraulic coin press. A coin blank or planchet is inserted upon the lower die, and the upper die is then forced against the planchet with many tons of pressure.

As the coin blank is squeezed by the press, the metal "flows" outward to the collar or retaining die. This may have vertical grooves known as reeding, though some coins – such as Presidential and Native American dollars – have edge inscriptions instead.

At the same time, the metal also flows into the recessed design on the dies to create a "raised" image on the coin.

After this minting process, the finished coins are mechanically sorted and counted, frequently inspected, and conveyed to bagging and rolling machines.

This planchet, when it leaves the coin press, will have become a Washington quarter.

Special collector issues, such as Proof coins, are made using a similar process. However, these are struck at least twice, and under greater pressure. They are also fed into and removed from the coin press by hand to avoid any contact with other coins, then specially packaged to protect their exceptional Proof finish.

Read more...