What is Money Made Of and How is Money Made?

Updated February 9, 2023

The production of modern U.S. paper money is a complex procedure involving highly trained and skilled craftspeople, specialized equipment and a combination of time-honored printing techniques merged with sophisticated, cutting-edge technology. Printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) in either Washington, D.C. or Fort Worth, Texas, paper currency is produced to strict quality standards with several security measures built in to deter counterfeiting.

In this guide, you'll learn what money is made of and how money is made through a seven-step process.

7 Steps to Making Paper Money

Since 2003, new designs for denominations of $5‑$100 include security features to make these bills more difficult to counterfeit.

What is Money Made Of?

While most paper used for items such as newspapers and books is primarily made of wood pulp, money is made out of a special currency paper composed of 75% cotton and 25% linen. Produced by Crane Currency in Dalton, Massachusetts, this paper is made specifically for the BEP – and only for the BEP. It's illegal for anyone other than the BEP to have it in their possession.

Similarly, the BEP designs and produces their own inks. All U.S. paper money features green ink on the backs, while the faces use a combination of inks. Including black ink, color-shifting ink (in the lower right corner of $10-$100 notes) and metallic ink (for the freedom icons on $10, $20 and $50 bills). The "bell in the inkwell" freedom icon on $100 notes also uses color-shifting ink.

Currency Design

The visual appearance of each denomination is created by a bank note designer and, in cases like that of the current $100 bill, can take as long as 10 years to make it into circulation. Recent new designs for denominations of $5-$100 use similar portraits and historical images to previous notes, but include subtle background colors to make the bills more difficult to counterfeit. Security features include a portrait watermark visible when held up to the light, two numeric watermarks on $5 notes, enhanced security thread that glows under an ultraviolet light, micro printing, color-shifting ink that changes color when the note is tilted and a 3‑D security ribbon on the current $100 bills.

Offset Printing

For notes of $5 and above with subtle background colors, offset printing is the first stage of production once a design is finalized. The colored background design is duplicated on a film negative and transferred to a thin steel printing plate with light-sensitive coating through exposure to ultraviolet light. This is called "burning a plate." The background colors are then printed on the BEP's Simultan presses, which are state-of-the-art, high-speed rotary presses. Ink is transferred from the printing plates to rubber "blanket" cylinders, which then transfer the ink to the paper as it passes through the blankets. The printed sheets are then dried for 72 hours before continuing.

Plate/Intaglio Printing

Intaglio printing is used for the portraits, vignettes, scrollwork, numerals and lettering unique to each denomination. From an Italian word meaning to cut or engrave, "intaglio" refers to the design being skillfully "carved" into steel dies with sharp tools and acids – which is why the process is sometimes called plate or steel plate printing. Some engravers specialize in portraits and vignettes, while others are experts in lettering and script. The images are then combined and transferred to a printing plate through the process of siderography. Engraved plates are mounted on the press and covered with ink. A wiper removes the excess ink, leaving ink only in the recessed image area. Paper is laid atop the plate, and when pressed together, ink from the recessed areas of the plate is pulled onto the paper to create the finished image.

The green engraving on the back of U.S. currency is printed on high-speed, sheet-fed rotary intaglio presses. Back-printed sheets require 72 hours to dry and cure before moving to the face intaglio press, where special cut-out ink rollers transfer different inks to specific portions of the engraved designs. Black ink is used for the border, portrait and Treasury signatures, while color-shifting ink is used for lower right portions of $10 and higher-denomination notes. The freedom icons are printed with metallic ink on $10, $20, and $50 bills and color-shifting ink for the on $100 notes.

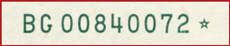

The letters on a modern serial number from the color series represent the series year, the Federal Reserve Bank to which the note was issued, and a counting device.

The star indicates this sheet replaces one found defective.

An uncut sheet of 32 $1 bills

Currency Inspection

The BEP's Offline Currency Inspection System (OCIS) integrates computers, cameras and sophisticated software to thoroughly analyze and evaluate untrimmed printed sheets. This system ensures proper color registration and ink density, and within 3/10 of a second determines whether a sheet is acceptable or must be rejected. The same equipment trims and cuts the 32-subject sheets in half to create two 16-subject sheets. The approved sheets then move to the final printing stage, which is accomplished by the BEP's Currency Overprinting Processing Equipment and Packaging (COPE-Pak).

Overprinting

COPE-Pak adds the two serial numbers, black Federal Reserve seal, green Treasury seal, and Federal Reserve identification numbers to each note. Modern serial numbers consist of two prefix letters, eight numerals and one suffix letter. The first prefix number indicates the series (for example, Series 1999 is designated by the letter B). The second prefix letter indicates the Federal Reserve Bank to which the note was issued. The suffix letter changes every 99,999,999 notes, so the serial number DG99999999A is followed by DG00000001B.

As sheets pass through the process, they are inspected by the COPE Vision Inspection System (CVIS). If a sheet is identified as defective, it is replaced with a "star" sheet. Serial numbers of notes on star sheets are identical to the notes they replaced, except that a star appears after the serial number in place of the suffix number. Notes from these sheets are called Star Notes, and are highly sought after by collectors.

Cutting, Trimming, and Packaging

Completed currency sheets are stacked and pass through two guillotine cutters. The first horizontal cut leaves the notes in pairs, while the second vertical cut produces individual finished notes. From there, a machine creates and shrink wraps bundles of 1,000 notes. Four bundles are then combined into bricks of 4,000 notes, and four bricks are combined into a group of 16,000 notes. These are shrink wrapped again and stored in the BEP's vault until they are picked up by the Federal Reserve.

Collecting Paper Money

While dollar bills are made of basic materials like cotton and linen at their core, it's the intricate design and production process – as well as the ties to our nation's history – that make paper money so collectible. If you're new to the hobby, browse our selection of Federal Reserve notes to see some of the most popular choices among collectors. You'll find single notes and sets in different denominations, including prized Star Notes. And if you have any questions, our team of experts will be happy to help!

Want to learn more about the coin creation process? Read Part 2, which covers how coins are made!

Sources

- Washington, DC. "Visiting the U.S. Bureau of Engraving & Printing in Washington, DC." https://washington.org/. Accessed 26 September 2022.

- Crane Currency. "Dalton." https://www.cranecurrency.com/. Accessed 26 September 2022.

- Frost, Natasha. "The incredibly secretive process of designing the next US banknote." Quartz. https://qz.com/. 13 March 2019.

- Britannica. "intaglio printing." https://www.britannica.com/. Accessed 26 September 2022.

Read more...